One of my colleagues with whom I’ve taught over many years at seminars on heal- ing is Dr. Carl Hammerschlag. When Carl first graduated Yale University Medical School back in the sixties, he humbly took a job as a physician for a rural Indian pueblo in New Mexico and immediately began to treat a long line of patients of all ages. Throughout his first and very busy day, he noticed an elderly man sitting in the corner, observing his every move. Finally, Carl approached the elder and asked if he, too, had come to be treated. Who are you?” asked the elder. “I’m a doctor.” Carl replied. “A healer,” he restated, in case “doctor” wasn’t the right word in the pueblo culture. “Do you know how to dance?” asked the elder. “Dance?!” blurted Carl, puzzled by the question. “No. I’m a healer, not a dancer.” The elder slowly rose and headed for the door, then turned around, looked Carl straight in the eye and said, “If you don’t know how to dance, then you don’t know how to heal!” Needless to say, Carl has been dancing ever since. Healing is essentially the restoration of aspects of our complex Selves that have either become lost, neglected or traumatized. When this happens, we become unplugged, severed from the balance of our core Self. Both music and dance are essential languages that speak to and are under- stood by every part of our being and can, during such episodes, shift our minds and emotions out of their routines or patterns so that we might restore the balance we lost and fine-tune the many parts of our totality. It has always mystified me how every single ancient people, regardless of how many thousands of miles they lived apart from one another, shared similar instruments of music, tools of war and the importance of dance. While we can hope to avoid war, I doubt if we can do without the universally common attributes of music and dance. Both were believed, from time immemorial, to be not only good for the soul and body but also important to the process of physical and emotional healing. I often encourage participants of my classes and workshops not to leave their troubles outside the dance, but rather to invite them into the dance to transform and heal them. Dance is a remarkable time-proven method for awakening the body, while music and chant work wonders for inspiring the spirit, and meditation for clear- ing the mind. In the indigenous language of my people, the word for dance and the word for illness are actually the same: ma’cho’l for dance, machah’lah for illness. Not by accident do they both share the same word. After all, dancing brings one to a state of joy and, when the body is in a state of joy, the negative energies contributing to illness are more likely to dissipate. The Life Force that moves us along our life-walk, taught the ancients, is drawn more into manifestation in our lives when we are in a state of joy, and the gift of dance is that it is either inspired by joy or brings us to joy. I’ve been a dancer my entire life, beginning at age two when I attended local ballet classes and would also joyfully dance through my father’s cornfield on the farm where I grew up. In the adult phase of my life, I continued to dance both recreationally and professionally, while blending contemporary scientific studies with ancient inspirational wisdoms to create modes of promoting wellness in a way that considers the entirety of a person, rather than only individual parts. This way of fostering physical and emotional well-being has helped many who are struggling, whether with debilitating illness, trauma, grief, life transitions, simply wanting more happiness in their lives, or reaching a crossroad with difficult choices. There is so much mystery and value in each of us, and so little time and resources to engage them and bask in them. Life is incredibly rich, but we need to carve out the time and space in our lives to experience it and to be nurtured by it physically, emotionally and spiritually. This is all the more important in these precarious times. There is a great deal of tension building in the world. More people are on edge. The future has become less certain than in years past. Our vision is blurring. Too much information and stimulation are jamming our heads daily, and the pressure we feel is at an all-time high. We are very fortunate, those of us who live up here on the mountain, and, hopefully, we take the time to feel the inspiration Nature invites us to enjoy daily. After all, the mountains — says a 3,000-year-old song — “they dance like gazelles!” And so should we. It is told that once, during a religious service, the 18th-century wisdom master, Mendel of Kotzk, chose to sit quietly in a corner, watching his disciples dance around and around, singing and clapping their hands as they danced. Finally, they approached him and asked why he was not joining them in dance. His response: “I would if you knew how to dance.” Hearing this, they attempted a more frenzied dance, with more fervor and elevated voices and louder hand-clapping, but still the master chose to sit out the round, watching his dancing disciples with a critical eye. Again they stopped and invited him into the dance circle and, again, he declined, repeating his dissatisfaction with the way they were dancing. After several attempts to dance even better, and even better than better, they finally gave up and begged the sage to just teach them the proper way to dance. “Shut your eyes,” he said, “and imagine you are standing perfectly balanced at the very edge of the Abyss. Now dance!” Dr. Miriam Ashina Maron, Ph.D., BSN, RN, MA, is a spiritual healer and mentor in private practice and teaches Zumba as well as Meditation and Entrancing Movement at Bullworx Studio in Cedar Glen. As a sing- er/songwriter, she has nine albums of songs and chants to her credit, as well as a new cover single, “Life Uncommon,” available through iTunes, Apple Music, CD-Baby, Spotify or her website, www.MiriamsCyberWell.com. She is also a published author. Her most recent books: “Ancient Moon Wisdom” and “The Invitation: Living a Meaningful Death.” She can be reached at (310) 281–3016 or via her website.

0 Comments

One day a young doctor noticed an elder from the local Indian pueblo sitting in the waiting room of his clinic, watching him examine patient after patient. At the end of the day, the doctor, Carl Hammerschlag, then a recent graduate from Yale University Medical School, approached the elder and asked if he was next. The elder eyed him for a while and then said: "I am curious. They said a healer has come to the pueblo." Carl chuckled proudly: "That's me! I am a doctor." There was quiet. Then the elder asked him: "Do you dance?" Carl laughed again: "No." The elder rose and turned to leave, and said: "Then you can't heal." This experience, which took place on the pueblo in New Mexico where Carl did his post-graduate internship, changed Carl's life and his entire way of practicing medicine. Years later, at a Walking Stick retreat that he and I co-led, Carl (now a nice Jewish doctor in Arizona) realized that the pueblo elder could just as easily have been Reb Mendl of Kotzk, or Reb Nachman of Breslav -- that the Jewish tradition shared the same mindset around the power and sanctity of dance and its role in healing and in spiritual practice. The word for dance and the word for illness, taught Rebbe Nachman of Breslav, are related: ma'cho'l for dance, machah'lah for illness or affliction. Not by accident do they both share the same root. After all, dancing brings one to a state of joy, and when the body is in a state of joy, the negative energies contributing to illness begin to dissipate (Likutei MoHaRaN Tanina, chapter 24). After all, the Shechinah -- the godly life force that moves us along our life walk -- is drawn more into manifestation in our lives when we are in a state of joy (Talmud Bav'li, Shabbat 30b). Rebbe Nachman also pointed out that when the Torah says of our ancestor Yaakov, "he lifted up his feet" (Genesis 29:1), it implies dance, as the second-century Rabbi Acha commented: "His heart lifted his feet" (Midrash B'reisheet Rabbah 70:8), meaning that when his heart was stirred to joyfulness after his reassuring vision of the ladder that connected earth to heaven, and after God's promise to him, it moved his feet to dance (Likutei MoHaRaN, chapter 32). Commenting on the words of the prophet Isaiah -- "Joy and celebration shall they seek, and trials and tribulations shall then be driven away" (Isa. 35:10 and 51:11) -- Rebbe Nachman wrote the following in Likutei MoHaRaN Tanina, chapter 23: When one is pulled into a circle of dancers, one should not leave one's troubles outside, but invite them into the dance to thereby transform them and heal them. It is usually the case that in such situations, one would be inclined to leave their troubles outside the dance. But one ought to in that moment pursue their troubles, seize them, and bring them into the dance, to heal them and transform them into joyfulness. As David wrote in Psalms, "You turned my grieving into dance" (30:12). When Reb Moshe Leib of Sassov heard that his friend the Rebbe of Berditchev had become ill, he repeatedly muttered his friend's name over and over again and prayed for his recovery. Then he suddenly put on his new shoes, laced them up tight, and danced himself into a frenzy. A disciple who was present at the time reported how "power flowed forth from his dancing. Every step was in itself a powerful mystery. A strange kind of light then spread across the house and everyone watching it saw angelic spirits joining in his dance" (my own rephrasing of Martin Buber's Tales of the Hasidim). The power and sanctity of dance was always an integral part of our people's theology and spiritual practice, from biblical times to the present. The Jerusalem Talmud recounts, for example, how women would dance in the vineyards and orchards during Yom Kippur and on the full moon of the month of Ahv, when the sun's heat began to diminish. The ancient rabbis themselves are reported to have done their share of dancing during the harvest season (sukkot) as part of the ritual of the water-drawing (simchat beyt ha'sho'ey'vah), even entertaining the folk by juggling flaming torches while they danced (Talmud Bav'li, Sukah 51a and Tosefta Sukah 4:2). The ancient teachers also considered dance to be one of the reasons the Torah came down to us in the Moon of Twins, in Sivan. Why then? "Because the twins resemble humans, to whom God gave a mouth with which to speak, hands with which to create, and feet with which to dance" (Midrash Pesikta Rabati 20:2). The prophets, the Tanakh recounts, used music in their spiritual practice and often drummed themselves into ecstasy (2 Sam. 6:16, and 1 Chron. 15:29), and I assume they also danced. How could they not? After all, dancing and drumming seemed to be a very common spiritual practice back then: "Praise Yah with drum and dance" (Ps. 150:4). Or, "Declare praise to God's name with dance" (Ps. 149:2). "And Miriam the Prophetess took drum in hand and led the Israelite women in dance and song" (Exod. 15:20). Nor was Miriam the only dancer in the family; her brother Aharon danced too, the ancient rabbis tell us. The two used to do special dances for their mother, Yocheved (Talmud Bavli, Sotah 12a). "The mountains, they dance like antelopes!" (Ps. 114:4). "There is a time to dance" (Eccles. 3:4). There absolutely is. Maimonides reiterates how the ancient prophets of Israel and their followers would dance themselves into an ecstatic state of mind before channeling prophetic visions, and that they would do so with the aid of drums and chant. "All of the prophets do not prophesy just any time that they wish," he wrote. "Rather, they focus their concentration and sit in a state of joyfulness and good-heartedness and meditate. For prophecy does not happen amid solemness, only amid joyfulness. Therefore, the prophets would have before them leather wind instruments, drums, flutes, and hollow leathered string instruments, during those times when they would seek their visions" (Mishnah Torah, Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah 7:4). Movement is also an integral part of prayer: swaying, bowing, dancing about. Moving your body in prayer is based on the verse in Psalms 35:10, "All of my bones declare: �O Infinite One! Who is like you?'" and is mentioned as a sacred practice not only during prayer but also during Torah study (sixteenth-century Rabbi Moshe Isserles [RAMA] in Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chayyim, chapter 28 and 48:2). The Talmud recounts how the second-century Rabbi Akiva would employ so much movement and dance in his worship that he would begin his prayers in one corner of the house and end up in the complete opposite corner "on account of all the swaying and bowing" (Talmud Bav'li, Berachot 31a). There are various ways of bowing. For example, the Talmud tells us that the second-century Rav Shey'sheht would bow like a bamboo shaft bending in the wind when he recited baruch, and then slither upward like a snake when he straightened to atah (Talmud Bav'li, Berachot 12a). The sixteenth-century Rabbi Yehudah Loew of Prague explained that there were two predominant types of dance, both sacred, yet one intended more toward transcendence than the other. Ree'kud, the standard Hebraic word for dance, is a dance of any kind, such as a celebrative dance at a wedding or other sacred celebratory event. Ma'cho'l is a transcendent form of dance, one that brings one to a state of ecstasy, so that the soul frees itself from its subjection to the body and connects in that moment to the realm of Spirit. This is why the word for dance used in the account of Miriam the Prophetess leading the women in dance is ma'cho'l (Exod. 15:20). And that is the very form of dance we do in prayer when we recite kadosh, kadosh, kadosh -- "Holy, holy, holy is Infinite One, Mover of all the Forces" (Isa. 6:3); we dance in an upward, leaping motion representing ascension, transcending our earthly manifestation.  Rabbi Loew also describes ma'chol as a form of dance that is usually done in a circle around a central point of focus, and relates it to the futuristic vision of the ancient rabbis: "In the world to come, God will lead the righteous in dancing and they, too, will dance before God" (Midrash Eichah Rabati 1:3). Rabbi Loew goes on to describe the dance as a circular one with God in the middle of the circle, pointing, so to speak, at each and every individual dancer, acknowledging each person (MAHARAL in B'er Ha'Golah, B'er Re'vee'ee, folio 76). A third and lesser-known form of sacred dance in Judaism is Meh'char'ker, translated as "whirling dance," where the dancer completely loses himself or herself in the frenzy of a whirling movement, totally entranced to the point of dropping all inhibition. The term chahr'ker is therefore appropriately used in the story of the Hebrew chieftain David (of the tenth century B.C.E.) when he was overcome with ecstasy after having recovered the Ark of the Covenant from the hands of the Philistines. During a victorious parade with the holy Ark, David gyrated in a wild whirling dance in public through the streets of Jerusalem, wearing nothing but a loin cloth (2 Sam. 6:14-16 and 1 Chron. 15:29). Interestingly, this strange term for wild, whirling, ecstatic, transcendent dancing happens to be one of the seventy names of the highest of the angelic spirits, Matat'ron, who is also believed to be the angelic incarnation of the ancestor Enoch. Matat'ron's thirty-eighth name is Meh'char'ker, or literally "Whirling Dancer" (Midrash Ba'tei Midrashot, volume 2, chapter 46, number 30). The power of movement and dance, Rebbe Nachman taught, is so potent it can even resurrect the dead! "Through a person's movement from here to there, one can resurrect the dead, as is written about Elisha when he resurrected the dead son of the Shunamite woman, that he �went to and fro, to and fro' (2 Kings 4:32-37). Movement causes the five wings of the lungs to flap; and through moving this way and that way, one moves into motion the five wings of the lungs which, when they flap, stir the heart so that the heart gives off sparks of lifehood and rekindles the life force throughout the body, and thereby even rousing the dead to life" (Likutei MoHaRaN, chapter 92). Dance and movement is therefore held quite sacred and highly spiritual in the Jewish tradition, certainly not to be taken lightly -- although one needs lightness to dance in the first place. It is told that on one Simchat Torah, Reb Mendl of Kotzk (of the early nineteenth century) chose to sit quietly in a corner of the synagogue, watching his Hasidim dance around and around the beemah, singing and clapping hands as they danced. Finally, they approached him and asked him why he wasn't joining them in dance. He responded, "I would if you knew how to dance." Hearing this, they attempted a more frenzied dance, with more fervor and elevated voices and louder hand-clapping, but still the Rebbe of Kotzk chose to sit out the round, watching his Hasidim with a critical eye. Again they stopped and invited him into the dance circle, and again he declined, repeating his dissatisfaction with the way they were dancing. After several attempts to dance even better and even better than better, they finally gave up and begged the rebbe to just teach them the proper way to dance. "Close your eyes," he said. "Now imagine you are standing perfectly balanced at the very edge of the Abyss. Now dance!" Maron, Miriam. The Healing Power of Sacred Dance. Tikkun 25(2):61 http://www.tikkun.org/article.php/mar2010maron |

ArchivesCategories

|

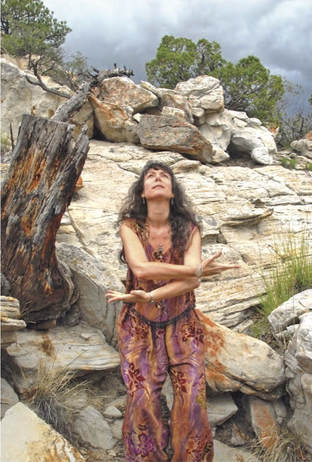

Rabbi Miriam Ashina Maron, R.N., M.A., PhD.